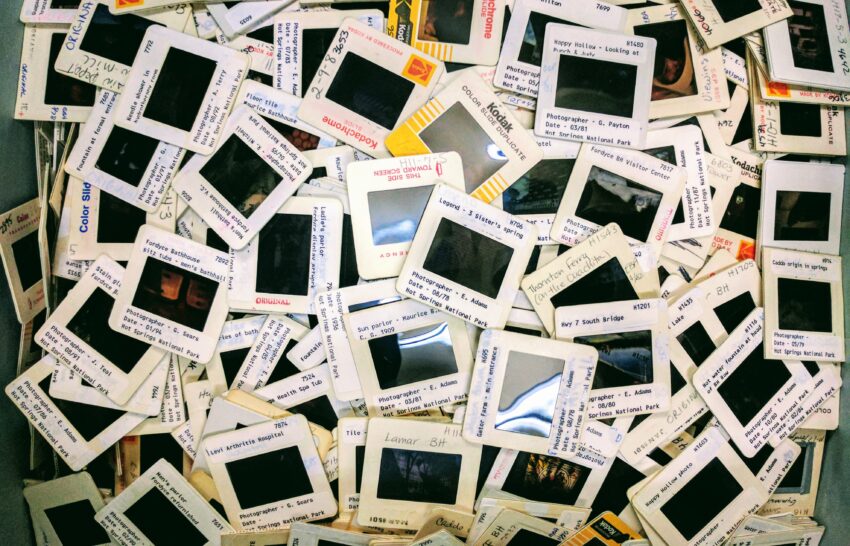

The phrase “archival detritus” first popped into my head several years ago, while on a research trip in Arkansas. I took the photo above—a box of photographic slides that had been digitized—and posted it to to Instagram, with “archival detritus” as the caption. I didn’t mean much by it then, but the phrase wormed its way into my brain. I chose it as the name for this blog as a reminder to myself of what I want this space to be.

The archive is full of detritus—trash, clutter, leftover. Though we historians often encounter archives in orderly boxes or folders, thanks to the diligent and disciplined work of archivists, these materials are rarely in orderly condition when they arrive. They are often accompanied by extra, unwanted material—scraps of paper shoved into the box, unrelated receipts, stray paper clips, cockroach carcasses and mouse droppings. Detritus. One of the skills of the archivist is to sort the trash, the extra, from that worth keeping.

Of course, the question of what gets categorized as detritus versus archival addition is a loaded one. Even of records that make it to an archive, not everything can be kept, especially of the reams of paper produced by many twentieth century sources. Such decisions, of course, are influenced by who does the archiving—what they consider important and worth saving, or judge as potentially meaningful, even if that meaning is not immediately clear. As many observers have noted, archives have been shaped by questions of race, gender, class, power, empire, and more. The archive is no objective record, but the result of a series of choices made by humans, each with their own judgments of what counts as source material and what is discarded as detritus.

Even if we could eliminate these blind spots, decisions about what to save are fraught. What might seem inconsequential today might be exactly the document a historian needs in fifty years. Archivists must balance space, resources, and time—always in such desperately short supply—with potential.

Similarly, on my own visits to archives, I am not always sure what is important. Sometimes a memo that seems extraneous in the moment takes on meaning only later, when I have learned more. Others never find a place in the story I am telling about the past. Sometimes, I know a document has nothing to do with my project but catches my attention anyway, too interesting to resist adding to my files. Maybe I will use it someday. Such archival detritus of my own making clogs my hard drive and my cloud storage, as it does for most historians, I suspect.

Archival detritus can also be evidence of careful management and responsible stewardship. In my photograph of the slides, for example: film deteriorates rapidly, and the slides had been scanned in an effort to extend the lives of their images. Materials fade, formats change, and archivists—again, as space and time permit—work to keep them preserved and accessible. Responsible stewardship has detritus as a byproduct.

There is another meaning of detritus, one that comes to us from ecology. This is the stuff of nature—fallen debris, leaves, carcasses, scat, bark, dead plants, insects—but with time, heat, moisture, and the work of microorganisms, it comes together as something more. That natural detritus isn’t unnecessary waste. It is the makings of something vital, that reinvigorates the soil and keeps the forest healthy and growing. With time and space, detritus becomes something immensely valuable. But to the untrained—or impatient—eye, its value is too easily overlooked.

I take all of these meanings to heart in dubbing this blog “Archival Detritus.” I mean it to be a home for interesting archival finds that might not fit my current project—at least not yet. It might be a space to take a closer look at material whose value I can’t quite see. It is a home for maintenance and management of my own thinking, converting to new formats and filing into new assemblages in the hope that such preserved ideas might come in handy later. Above all, I hope it will serve as a place where I can bring unexpected, overlooked bits together to meld, to decompose a bit and re-form, to give ideas the time and space that allow for the possibility that they may emerge as something precious—if I’m lucky and the weather cooperates.